RCVS: An Unusual But Treatable Cause Of Headache

- Corresponding Author:

- Asheesh Kumar

Government Medical and Regional Hospital

Hamirpur, Himachal Pradesh, India

E-mail: drasheesh03.kapil@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is characterized by severe headaches, with or without other acute neurological symptoms, and diffuse segmental constriction of cerebral arteries that resolves spontaneously within 3 months. The mean age of onset is 42 years, and it affects more women than men. RCVS is possibly caused by a transient dysregulation of cerebral vascular tone, leading to multi-focal arterial constriction and dilation. Approximately 60% of the cases are secondary to a known likely cause. Case Report: We report the case of 20 year old female with severe headache, due to vasospasm of vessels with intraparenchymal haemorrhage and spasm that relieved spontaneously in 7 weeks documented with repeat MRI. Conclusion: RCVS is a secondary cause of headache. Patients who have thunderclap headache with normal brain CT and cerebrospinal fluid without xanthochromia should be investigated for reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome.

Keywords

Haemorrhage; Xanthochromia; Cerebral

Introduction

Headache is relatively common in daily life, sometimes fatal. The severity varies from a mild headache to severe thunderclap headache. Thunderclap Headache (TCH) is characterized by excruciating pain that reaches its peak intensity within less than one minute [1]. Its incidence is 43/100,000/year. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) is responsible for 11% to 25% of the cases [2]. Among its secondary causes, Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS) is characterized by TCH associated with multifocal vasoconstriction of cerebral arteries in patients without aneurysmal SAH. The vasoconstriction reverts within three months. The CSF is normal or close to normal [3]. The pathophysiology of this syndrome is unknown. It has been postulated that it is caused by a transitory disorder of the cerebrovascular tone [3].

TCH recurs in 94% of the patients with RCVS. In addition to headache, focal neurological deficits (21%-63%) or epileptic crises (3%) may be found. The complications that have been described are ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, cortical SAH, cerebral edema, and arterial dissection. RCVS may occur spontaneously or, more frequently, there is a precipitating factor such as eclampsia or preeclampsia, puerperium, use of vasoconstrictor drugs, blood transfusion, tumors, hypercalcemia, porphyria, cranioencephalic traumatism, neurosurgical procedures, and carotid endarterectomy [4].

There are no clinical trials evaluating treatments for this syndrome. The use of vasoconstrictor drugs should be discontinued. Drugs that have been used to treat this syndrome include nimodipine, glucocorticoids, and magnesium sulfate [4].

We report a case of 20-year-old girl with severe headache, due to vasospasm of vessels with intraparenchymal haemorrhage and spasm that relieved spontaneously in 7 weeks documented with repeat MRI.

Case Report

A 20-year-old female presented with sudden onset headache, mild intensity to start with which became severe within 1 or 2 minutes. It was located in the left temporal region and was associated with photophobia without nausea, vomiting, visual disturbances, and weakness of any limb decreased sensation over any part of the body, abnormal body movement, altered behavior, or loss of consciousness. It remained severe for 8 hours and then persisted with less severity for 3 days. Her clinical and neurological examinations were normal. The patient never had similar episodes in the past. She was not on any illicit drugs or other medications.

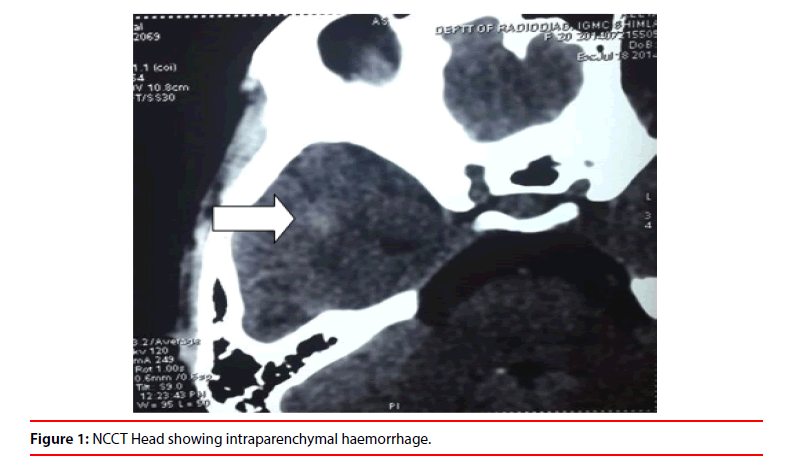

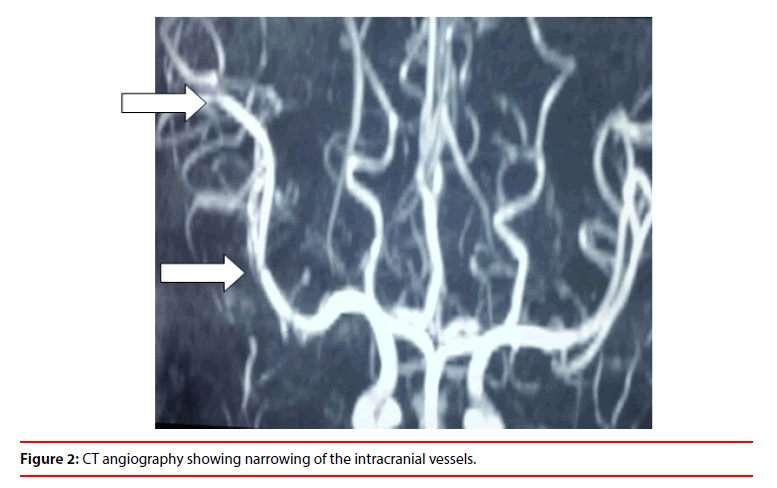

Her blood cells count, general biochemical tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antinuclear factor, and rheumatoid factor were normal. Urgent NCCT head revealed focal area of hypodensity along with one of the sulci in the right temporal lobe, with the possibility of SAH. Following this, an urgent MRI along with MRA was done which showed intraparenchymal haemorrhage in the right temporal lobe with hyperintensities along with sausage beads appearance on MRA. CSF examination was normal. ANA, CRP, p-ANCA, c-ANCA, and urine VMA levels were also normal (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was managed with tab nimodipine, became asymptomatic after 7 hours, and continued on the same. Repeat MRI after 7 weeks revealed absence of vasospasm indicating the reversibility of syndrome.

Discussion

Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS) is characterized by severe headaches, with or without other acute neurological symptoms, and diffuse segmental constriction of cerebral arteries that resolves spontaneously within 3 months [5]. The mean age of onset is 42 years, and it affects more women than men. RCVS is possibly caused by a transient dysregulation of cerebral vascular tone, leading to multi-focal arterial constriction and dilation [5]. Approximately 60% of the cases are secondary to a known likely cause. It is associated with nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and neurosurgical procedures, the postpartum period, many vasoactive and other drugs, sexual activity, and numerous other conditions including pheochromocytoma and porphyria. Frequently no cause can be identified [6].

Clinical manifestations typically follow an acute and self-limiting course without new symptoms after 1 month. Headache is the main symptom and often remains the only manifestation of RCVS. Onset is acute with thunderclap headache-extreme head pain peaking in less than 1 min, mimicking that of a ruptured aneurysm typical headache is bilateral (although it can be unilateral), with posterior onset followed by diffuse pain. Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia frequently occur. Thunderclap headaches can be as short as a few minutes but cases lasting several days have been reported. A single attack is possible, but usually patients have a mean of four attacks, during 1-4 weeks. Moderate headache frequently persists between exacerbations. Patients typically report at least one trigger-eg. Sexual activity (usually just before or at orgasm), straining during defecation, stressful or emotional situations, physical exertion, coughing, sneezing, urination, bathing, or showering, swimming, laughing, and sudden bending down. Focal deficits, which can be transient or persistent, and seizures have been reported in 8%-43% and 1%-17%, respectively, of the cases in the three large series. Transient focal deficits are present in slightly more than 10% of patients, last from 1 min to 4 h, and are most frequently visual, but sensory, dysphasic, or motor deficits can also occur [5].

Since the most common clinical manifestation of RCVS is recurrent thunderclap headache, the diagnosis should always be considered in this setting. Other entities that can be present with thunderclap headache include aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, cervicocerebral arterial dissection, and pituitary apoplexy. Idiopathic thunderclap headache is an exclusionary diagnosis for those patients who do not exhibit features of any of the above diagnoses. Evaluation for these other conditions is warranted, which will usually include CT scan of the head, followed by CSF examination for subarachnoid hemorrhage. MRI and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain and vessels of the head and neck can be helpful to narrow the differential diagnosis [6].

The results of blood counts, measurements of ESR and concentrations of serum electrolytes, and liver and renal function tests are usually normal in patients with RCVS. Tests for angiitis, including measurements of rheumatoid factor, antinuclear and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and tests for Lyme disease are generally negative. Urinary concentrations of vanillylmandelic acid and 5-hydroxy indoleacetic acid should be measured to exclude a diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma. Serum and urine toxicology screens should be done to check for drug use. Slight abnormalities of CSF are reported in 0%-60% of patients [5].

Brain scans of many patients with RCVS look healthy despite the presence of diffuse vasoconstriction on concomitant cerebral angiograms. Lesions are noted in 12%-81% of patients. Lesions include three types of stroke-convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage, intracerebral haemorrhage, and cerebral infarction and reversible brain edema [7]. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain during the first week is normal in most patients, but up to 20% may demonstrate a thin, convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage without evidence of aneurysm [8,9]. Intracerebral hemorrhage occurs in up to 10% of cases. In the same series, up to 10% of patients had MRI abnormalities consistent with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome [4]. Magnetic resonance angiography reveals diffuse segmental arterial constriction in up to 90% of cases. Large-and medium-sized arteries are more commonly affected [4]. Catheter angiography remains the gold standard test to demonstrate the characteristic ‘string of beads’ pattern of alternating areas of arterial stenosis and dilation in cases where noninvasive vascular imaging is inconclusive. Caliber irregularities can affect the anterior and the posterior circulation, and are mostly bilateral and diffuse. The basilar artery, carotid siphon, or external carotid artery can be affected. By definition, the cerebrovascular abnormalities are transient, and should demonstrate complete resolution on repeat imaging 1-3 months later. Transcranial doppler ultrasonography can be useful in monitoring cerebral vasoconstriction [5]. In some cases the diagnosis will remain unclear despite extensive evaluation by imaging and CSF analysis, brain biopsy may be necessary, although the sensitivity of biopsy for the diagnosis of primary CNS angiitis is certainly not 100%, and the true sensitivity is unclear [10].

No randomised clinical trials of treatment for RCVS have been done. Patients with consistent clinical and brain imaging features, no evidence for another cause of symptoms, and normal initial cerebral angiograms should be viewed as having possible or probable RCVS, and should receive the symptomatic treatment which is primarily based on the identification and elimination of any precipitating or aggravating factors. Patients should be told to rest (even if they have the purely cephalalgic forms) and advised to avoid triggers for a few days to a few weeks, depending on initial severity. Any vasoactive drugs should be stopped and avoided even after disease resolution. Treatment should include analgesics, antiepileptic drugs for seizures, monitoring of blood pressure, and admission to intensive-care units in severe cases. Drugs targeted at vasospasm can be considered when cerebral vasoconstriction has been assessed. Nimodipine, verapamil, and magnesium sulphate have been used to relieve arterial narrowing [5]. Treatment is typically given for 4-8 weeks, although the optimal duration is unclear. Transcranial ultrasound measurement of systolic velocities in intracranial arteries has been used to assess treatment efficacy. The efficacy of treatment varies considerably between reports, ranging from 40% to 80% [4]. In refractory cases, intra-arterial nimodipine, papaverine or milrinone have been used with good results reported, although experience is limited to case reports [9,10]. Steroids should be avoided [11-13].

In most patients, headaches and angiographic abnormalities resolve within days or weeks. Long-term prognosis of RCVS is determined by the occurrence of stroke. Most patients who have strokes gradually improve for several weeks, and few have residual deficits [4,6,14]. Less than 5% develop life-threatening forms with several strokes and uncontrolled massive brain edema. The combined case fatality in the three largest studies was less than 1% [12-14].

Conclusion

In conclusion, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome is a secondary cause of headache that can be associated with neurological complications such as ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, cortical SAH, cerebral edema and arterial dissection. Patients who have thunderclap headache with normal brain CT and cerebrospinal fluid without xantochromia should be investigated for this syndrome.

References

- Olesen J, Bes A, Kunkel R. Headache classification committee of the international headache society. The international classification of headache disorders (3rd edition) Cephalalgia 38, 9-160 (2018).

- Landtblom AM, Fridriksson S, Boivie J, et al. Sudden onset headache: A prospective study of features, incidence and causes. Cephalalgia 22, 354-360 (2002).

- Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Sin, et al. Narrative review: Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Intern Med 146, 34-44 (2007).

- Ducros A, Boukobza M, Porcher R, et al. The clinical and radiological spectrum of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. A prospective series of 67 patients. Brain 130, 3091-3101 (2007)

- Anne Ducros. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Lancet Neurol 11, 906-917 (2012).

- Sattar A, Manousakis G, Matthew B. Systematic review of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 8, 1417-1421 (2010).

- Singhal AB. Cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Top Stroke Rehabil 11, 1-6 (2004).

- Chen SP, Fuh JL, Lirng JF, et al. Recurrent primary thunderclap headache andbenign CNS angiopathy: Spectra of the same disorder? Neurology 67, 2164-2169 (2006).

- Ducros A, Boukobza M, Porcher R, et al. The clinical and radiological spectrum of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. A prospective series of 67 patients. Brain 130, 3091-3101 (2007).

- Edlow BL, Kasner SE, Hurst RW, et al. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 7, 203-210 (2007).

- Calado S, Viana-Baptista M. Benign cerebral angiopathy; postpartum cerebral angiopathy: Characteristics and treatment. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 8, 201-212 (2006).

- Bouchard M, Verreault S, Gariepy JL, et al. Intra-arterial milrinone for reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Headache 49, 142-145 (2009).

- Elstner M, Linn J, Muller-Schunk S, et al. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: A complicated clinical course treated with intra-arterial application of nimodipine. Cephalalgia 29, 677-682 (2009).

- Singhal AB, Hajj-Ali RA, Topcuoglu MA, et al. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes: Analysis of 139 cases. Arch Neurol 68, 1005-1012 (2011).